GIANAKOS – SEMIOSE

Portrait of The Artist as a Cockroach

Among the earliest epitaphs carved into the gravestones in France’s oldest pet cemetery, in Asnières in the Paris suburbs, we can find inscriptions that repeat well-known declarations such as: “The more I learn about people, the more I love my dog,” or “Disappointed by the world, never by my dog.” Darwin believed that the intense love humans feel for their pets was reciprocal, imagining that monkeys smile at us because they are happy; unfortunately, today’s research shows that this superficial smile simply testifies to the individual’s submission to a creature better placed in the pecking order. Although it is currently impossible to scientifically evaluate love and attachment, studies in 2015 measured blood-serum levels of oxytocin, the hormone related to affection and trust secreted by humans and their faithful companions: in a dog cuddled by its human, oxytocin levels can increase by more than 50 %. With cats, this increase is limited to around 12 %.

The bond of love between humans and animals is not built on very solid foundations: according to Professor Jean-Claude Nouët, Honorary President of the French League for Animal Rights, 50 % of rapists committed acts of cruelty against animals in their childhood and 15 % of them also raped animals. For Saint Thomas Aquinas, Locke, Kant and Schopenhauer, there is a general link between cruelty to animals and violent acts committed against humans; moreover, recent sociological studies indicate that the majority of serial killers as well as simple murderers, “learned their trade” by killing or torturing animals when they were young.

For Sigmund Freud, the motive for this is sexual, so it’s hardly surprising that Steve Gianakos was attracted by the subject. In his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905), Freud postulates that the urge to commit acts of cruelty and the sexual urge are linked in early childhood by anastomosis, an interconnection that is biological. This association of sexuality and cruelty—exercised from an early age and against animals of all shapes and sizes—is quickly curbed and ideally even controlled by the emergence of feelings of pity; the ability to empathize with the pain felt by others, including animals, which inhibits the universal desire to dominate and that appears relatively late in a child’s development.

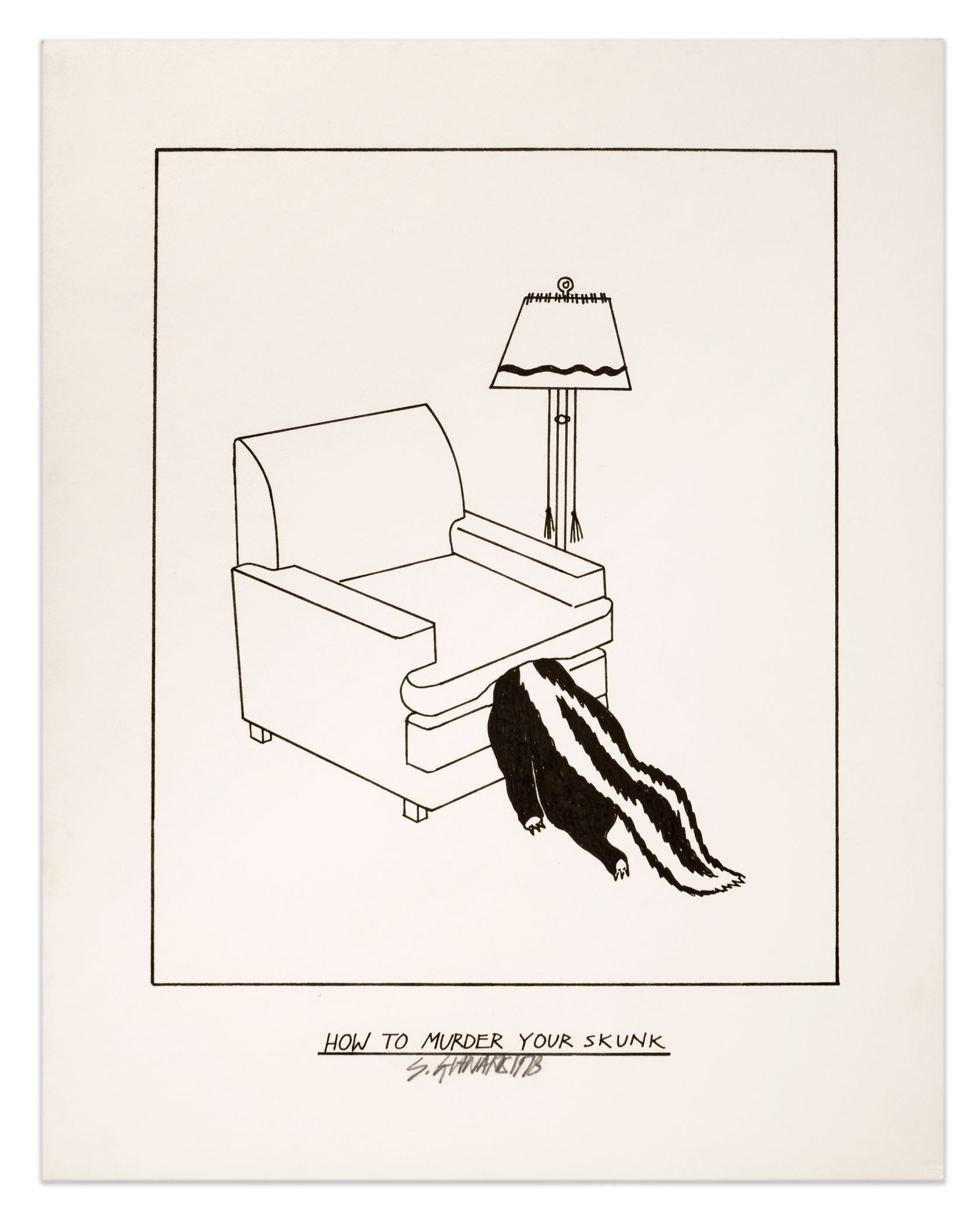

Artistically, empathy takes on an unconventional form in Gianakos’ work. In a now legendary interview with Susan Morgan in 1979, published in the second issue of the magazine Real Life1, whose cover featured a drawing from the How to Murder Your Pet series, the artist states: “My work is not nearly as offensive as the people who look at it. Just walking the streets, you see things which are much more disgusting than anything I could ever conceive of doing—people vomiting all over the place. I try to sweeten things up, I don’t try to vulgarize them. I try to take things I know exist and make them prettier, rather than trying to make pretty things more ugly. When you talk about rich ladies fucking their dogs, that’s an example of something it would be impossible to vulgarize because it’s already too vulgar. So, the only way to prettify it is to make a nice picture of a rich lady fucking her dog. At least that would appeal to some people.” In 1945, in Bruno Munari’s book for children Animals For Sale, an animal salesman desperate to find the ideal companion for an invisible child, finally discovers that rather than an armadillo, a pink flamingo or a porcupine, what the child really wants is a roast chicken with fries!

In the above-mentioned interview, Gianakos gives free reign to his caustic and iconoclastic humor when addressing the question of subjects of art. For example, he mockingly asks: “How many artists have already painted flowers and are going to paint flowers for the next hundred years? What’s with them and flowers? Why don’t they paint germs? How many artists have painted paramecium? Only Arp. Didn’t Arp paint paramecium? I think that was very perceptive of him.” Pushing his theory still further, he states: “I’m very fond of snots, but I’ve never sold a snot painting. I don’t think even Picasso could sell a snot picture, I really don’t.”

Produced in 1978, the 24 drawings that make up the series How to Murder Your Pet are perfect examples of Gianakos’ art. Firstly, as we have already seen, the subject matter is deeply linked to the primal emergence of sexuality. Secondly, the serial treatment of the subject is typical of his working practice. As he explains to Susan Morgan: “Obviously the best way to murder something is to tie a rock around its neck and throw it off a bridge, but since I’m so arty and these are all very visual, I make my idea a pretty picture.” In this series, Gianakos does not depict dead domestic animals, but rather ways of killing them, a variety of forms of torture that are all variations on the childish cruelty described by Freud. While some of them have obvious sexual connotations (the goat, stuck in a doorway with a sweeping-brush in its rectum, which at the time outraged a number of commentators), others depict the brutal—and certainly painful—encounter between an orifice and a foreign body: the guide dog with a walking stick protruding from its eye socket, the bowling ball forcing open the hippo’s mouth, the cow sucking on the exhaust pipe of a beetle (the car), the leg of a modernist chair being force-fed to a duck… There’s also symmetry in the corkscrew tail of a pig penetrating an electrical wall socket, leading to its electrocution.